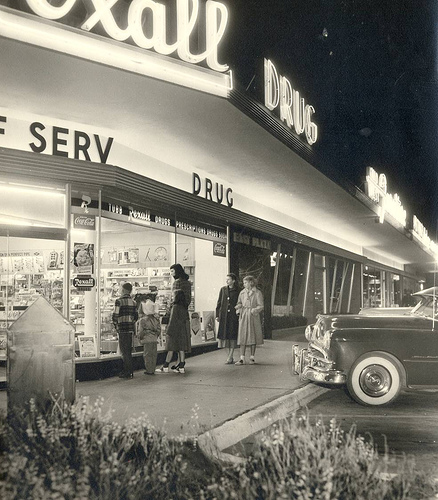

(All photos courtesy of the Atkinson Center)

W.P. “Bill” Atkinson was on the rise as the

And Atkinson was in good standing with Daily Oklahoman publisher E.K. Gaylord.

“Mr. Gaylord and I were close personal friends,” Atkinson said in a 1991 interview with KOKH interviewer Ronnie Kaye. “I wanted what was best for the state and

Everything would change with the opening of a new air force base. The feds were being coy as to where they would locate the base. But when the base’s location east of downtown

When the dust settled, Atkinson stepped forward as proud neighbor of the $25 million air depot. Gaylord and fellow chamber executives fumed, assuming Atkinson had exploited his position as a chamber board member to get information on the base’s location.

Atkinson, however, credited Gaylord, or rather the front page of his newspaper, for making the deal possible.

The story about the potential new air force base, Atkinson noted, was only a few inches long.

“He literally told me where Tinker would be located,” Atkinson said. “He didn’t know it. He said it will be located within 10 miles of downtown

Atkinson got out the maps and began circling the county. He gambled on a sleepy rural area east of downtown with major property owners whose names still grace area roads.

Robert Peebly, for example, was a leading settler who moved into the

Another settler arriving from

As World War II began to get underway, all that stood between Oklahoma City and Shawnee were the Log Cabin gas station and cafe on SE 29, Koelsch’s Store at Reno and Sooner, and the small community of Marion, where Carl Albert High School is today.

With war looming, the federal government began scouting for land on which to build an army air corps installation.

As noted by The Daily Oklahoman, the government wanted a spot 10 miles from an urban center, at least four miles away from any oil field, proximity to a rail line, a hard surface road, and inside a large span of flat land.

Atkinson gambled that the chosen location would be along SE 29 between Air Depot and

Atkinson started with a map, and marked up areas that fit the government’s strict criteria and determined SE 29 fit perfectly. He stopped at homes and found that those south of the line were suspicious about his inquiries and unwilling to sell. To the north, he found farmers eager to sell. His investigation had gone better than he could have expected.

The gamble wouldn’t be cheap, however. Atkinson bought original 1889 homesteads from the Trosper and Chesser families for an eye-popping $15- an acre.

Once the site for the depot was announced, the chamber went out trying to buy up surrounding land. They were amazed it had been sold to an unknown buyer. Gaylord and others tried to find out who it was.

Atkinson speculated the war department would want to buy his land as well, so he traveled to the Pentagon and urged them to let him build a city on his land to go hand in hand with the base.

Neither Gaylord, chamber executive Stanley Draper or

On May 14, 1941, Oklahoma City City Manager H.E. Bailey informed Atkinson his 168 acres would be needed for “expansion” of the base site and that the city would seek to condemn it unless he agreed to sell.

“With great good fortune, Atkinson and his group arranged to buy the land just before the location of the depot was announced,” a story in the May 15, 1941 Daily Oklahoman noted. “It looked like a gold mine for development of residences for some of the 3,500 skilled workers to be employed at the depot.”

Atkinson, however, wasn’t going to be deferred. On January 17, 1942, Atkinson came out with his grand plan for a $4 million “model town” adjacent to the depot along SE 29.

Atkinson’s town, to be christened “

Atkinson would hire Hare and Hare, the renown

The announcement had the blessing of the U.S. Air Force, which was now ramping up plans for the depot to employ 7,000 people.

Lt. Col. W.R. Turnbill, newly arrived commander, met with Atkinson and gave his blessing.

“The government desires establishment of housing projects near airfields and depots as a moral builder,” Turnbill said.

Atkinson hired FHA urban land planner Stewart Mott, who designed a city in two crescents. Atkinson gambled that with such a major base opening during the war, with travel restricted and gasoline being rationed, having a city across the street wouldn’t be such a bad idea. Workers could walk to the base from their homes while their wives could walk to area shops and children could safety visit nearby schools and parks.

At a time when

Atkinson’s wife Rubye, meanwhile, started garden clubs and women’s groups to help jumpstart

“Everybody was just chewin’ hard on me, trying to do everything could just to keep me from doing it,” Atkinson said in a 1991 interview with Max Nichols. “So, they used every psychological thing I’ve ever heard of to try to trip me up, that is, Stanley Draper and E.K. Gaylord.”

In this environment, Atkinson was surprised to be invited to be the main speaker at a chamber board luncheon.

“Whoever heard of that?” Atkinson said. “And it was two, three years after

G.A. “Doc” Nichols, who had started up his own town, Nichols Hills, came to Atkinson’s defense.

“Doc Nichols got up one time and he waved his hand,” Atkinson recalled. “Well, that meant for me to sit down and let him talk. He said, “Bill, now let me tell you something. You’re gonna’ build this town, and if there’s any doubt at all, I better give you a few tips right now.’ He was a clever guy.

“He said, ‘Who are you doing business with?’ I said, ‘well, I’m doin’ business at Liberty National Bank.’ He said, ‘You’re doin’ business at the wrong bank. Go over to Chuck Voss and borrow all the money you can from him, because he doesn’t know a damn thing about building homes, and he’ll never throw you into bankruptcy because there’s no way he … he’s got to stay with you.’ Of course, everybody just roared, you know, and Chuck Voss roared too.”